Kitchen Cabinet Construction 101

Kitchen cabinet construction isn't rocket science nor do you need to know every last detail about it. But even if you're not the type of person who's inclined to ponder "how things are put together", it's still helpul to understand the basic parts and how they're constructed.

That way you'll have a better feel for the different levels of cabinet quality and what you do or don't get for the various levels of cost you'll encounter.

If you haven't already, it may help to take a look at our cabinet glossary page to get familiar with some of the terms you'll encounter along the way. Otherwise it'll always be there if and when you need it.

The Basic Elements and Design Styles

Framed and Frameless Construction

How a cabinet is built varies among manufacturers but they all conform to 2 basic design styles. These styles or design types are called framed and frameless. Framed cabinets are also called face-frame cabinets so you may see them referred to both ways. There's not too much difference between the two styles in the way they're constructed. What's different is how they look and the amount of accessibility you have to the inside of the cabinet.Framed Construction

Framed cabinets incorporate a wood 'frame' around the front outer edge of the cabinet box. That's in contrast to a frameless cabinet which doesn't have this feature.If you visualize a basic wood box, the face frame is made up of several pieces of wood that are fastened to the forward edge of the cabinet, framing the cabinet box. The outside edges of the frame are flush with the outside surfaces of the cabinet box whereas the inside portion of the frame extends past the inside edges of the box slightly. The face frame provides some rigidity to the cabinet box, helping it to remain square and sturdy.

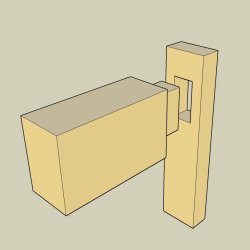

Example Of The Basic Structure Of A Framed Cabinet

Example Of The Basic Structure Of A Framed Cabinet

Framed cabinets are generally considered more traditional looking and offers some style variety based on the amount of door overlay. Door overlay just means the extent to which the door covers or "lays-over" the face frame.

- Full-overlay means the doors and drawers completely cover the face frame

- Partial-overlay simply means that the doors and drawers cover only part of the frame.

- Full-inset means the doors and drawers are made to fit within the face frame opening.

Different manufacturers offer varying styles in the extent of door-to-frame overlay.

Frameless Cabinet Construction

Frameless cabinets on the other hand offer a bit more accessibility than framed cabinets. Example Of Frameless Cabinet Construction

Example Of Frameless Cabinet Construction

Frameless cabinets are often described as a "European" style of cabinet. Cabinet doors are typically full-overlay (covering the entire front edges of the cabinet box) though some can be made as full-inset. With full-inset designs the edges of the cabinet box are usually finished with a wood or laminate veneer or some other material to mask the raw edges of the cabinet box.

So what's the significance of these differences? Not too much, other than some style differences and a little less accessibility to the inside of framed cabinets. They both work well and just evolved from different design traditions.

Base/Wall/Tall Cabinets

Beyond framed and frameless design, the other primary elements of cabinet construction to be aware of are their basic units or "building blocks". These are the predominant components that your cabinets will be comprised of.- Base cabinets are the cabinets mounted on the floor that usually support the countertops. Kitchen islands are also a form of base cabinet and can be a combination of several base cabinets joined together or a custom-made base.

- Wall cabinets as their name implies are mounted on the wall, with no connection to the floor. They're typically located above the countertops and stoves/ovens.

- Tall/pantry cabinets are essentially tall base cabinets. They stand on the floor and may be free-standing or attached to other wall and/or base cabinets.

Most kitchens are a combination of all of these basic units.

Cabinet Materials and Construction

Materials

Most of us think of kitchen cabinets as being made out of wood and that's true for the most part. But don't think that it's all "solid wood" like the lumber used to frame a house. There are other materials that go into the construction of cabinets. Some are wood-based but others are not.Here's a list of the primary cabinet materials you'll encounter:

| Solid wood - just as the term implies, it's solid homogeneous wood, all the way through. The only variation might be boards or panels that are several pieces of solid wood joined together. |

| Particle board - an engineered wood product that's made from wood chips and particles that are combined with an adhesive and fused together into boards and panels. Particle board makes up a large percentage of the materials used in today's cabinetry, from the panels that make up the boxes to shelving. |

|

| Medium density fiberboard (MDF) - another engineered wood product that's made up of wood fibers. The fibers are combined with an adhesive under pressure and formed into boards and panels. MDF has a finer texture than particle board and is denser and heavier than particle board. It's used in cabinet doors, shelves and cabinet boxes. |

| Plywood - yet another engineered wood product but one that's probably most familiar to people. It's made up of thin wood "plies" or layers of wood that are glued together in a sandwich form. Usually the plies are oriented with their grain direction at varying angles with respect to each other to give the board or panel more rigidity and stability. Plywood is used for shelving, doors and cabinet boxes. |

|

Construction Methods

Methods for building and assembling cabinets will vary based on manufacturer and the level of quality you pay for. There's no need to become a master carpenter to be an informed cabinet buyer but there are some terms and construction techniques that you'll probably encounter, even if it's just browsing a cabinet maker's brochure or website.The important thing to take home on this subject is that there is a relationship between the type of construction and the cabinet's level of quality and durability.

The following terms describe some common methods of wood cabinet "joinery" ('joinery' just being the trade term for how the various wood parts are joined together):

|

Dovetail joints - this is a strong method of joining two boards together at right angles, such as with drawer boxes. The ends of two boards or panels are notched with v-shaped cutouts that mesh with corresponding notches on the adjoining panel. If they're tight, these types of joints are considered very solid. |

| Mortise and tenon - another form of joinery, this method uses a square "post" protruding from one end of a piece of wood that fits into a square hole or cutout in the mating piece. This type of joinery might be used to fasten the pieces of a cabinet's face frame together. |

|

|

Dado - this is a groove that's cut into a board or panel that the edge of another board/panel can fit into. A good example is the sides and back of a cabinet drawer that are dadoed to accept the edges of the drawer bottom. It's a stronger way to 'capture' the drawer bottom than just gluing or nailing the drawer bottom edges to the side panels. |

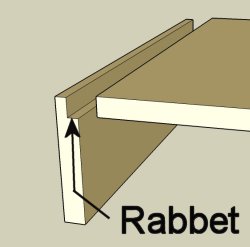

| Rabbet - this is not the kind that Elmer Fudd chases but rather, a notch or step that's cut into the edge of a board to accept the edge of another board to form a 90-degree angle. It's similar to a dada cut except one side is left "open". |

|

|

Doweled joint - this joinery technique uses round wood dowels (pegs) that are pressed and/or glued half way into holes drilled into one piece of wood. The protruding part of the dowel is then fit into holes drilled into the mating piece of wood. This method is another way to join the sides of drawers or cabinet boxes together. |

| Butt joint - on a butt joint, the ends of two pieces of material are brought or "butted" together, edge to edge. Some form of mechanical retention like nails, screws or glue is needed to hold this joint together. |

The bottom line on cabinet construction methods is that good joinery techniques where the parts 'lock' together or where one piece is captured in the other makes for the strongest joints. Supplemental fastening methods on these joints (such as a mortise and tenon joint plus screws) makes an even stronger connection. Stronger joints equate to more durable cabinets.

The Parts You'll Want To Pay Attention To

Cabinet Boxes & Face Frames

- Materials

Cabinet boxes are made from particle board, MDF or plywood. Solid wood panels normally aren't used to construct the cabinet box except for the face-frame on framed cabinets. Panels made from these wood products are usually covered in either a wood veneer, plastic laminate/melamine or thermofoil.Stainless steel is another material used to make cabinets though it's much less prevalent than wood. Stainless steel cabinetry provides a novel look and depending on the setting, resembles professional kitchens. On the plus side steel won't expand and contract like wood will in a kitchen environment. One of the down sides is the challenge in keeping the cabinets free from fingerprints which can be tough to clean.

- Construction

The cabinet box is essentially just that - a box. The key point to understand here is that there are several methods used to reinforce the box and make sure it remains rigid. One means of reinforcing the cabinet box involves the use of triangular braces in the corners of the box. They're made from either particle board, MDF, plywood, solid wood or plastic. Another reinforcing feature uses an "beam" brace that runs from the front of the box to the rear on the inside of the side panels or along the back from side to side. The beam brace usually fits in a dado slot in the side panel.

Drawers

- Materials

Cabinet drawers are predominantly made from the same materials that are used to construct the cabinet cases such as particle board, MDF, plywood and solid wood. On higher quality drawers more of the drawer parts tend to be made of solid wood to stand up the abuse from more frequent opening and closing. On stainless steel cabinets the drawers are made from stainless steel. Some cabinet manufacturers offer options for metal drawers on their wood cabinet lines. These drawers are coated with an epoxy coating.Drawer fronts, the part of the drawer that you see, tend to be made from solid wood or MDF that's either painted or covered with thermofoil.

- Construction

The way a drawer is built plays a large role in its durability and longevity. The drawer box is made up of two side panels, front and back panels and the bottom. Most cabinet drawers have a separate front piece that's attached to the front drawer-box panel although on some drawers the drawer front and front panel are the same piece.The parts that make up the drawer box can be assembled in several ways. Dovetail joints that are tight form the strongest connection at the corners of the drawer. Doweled joints where one side of the drawer box has dowels installed on one end that fit in holes in the mating panel end is another form of joinery. Drawer bottoms that fit into dado slots in the drawer slides are stronger than bottoms that are just nailed and/or glued to the bottom of the drawer box. Glue, small nails and staples are also used to fasten drawer parts together.

Doors

- Materials

Cabinet doors, except for stainless steel cabinets, are made from solid wood or one of the engineered wood products (particle board, MDF, plywood). Engineered wood doors are covered with a wood veneer, laminate or thermofoil.One of the benefits of MDF is that it can be routed and cut, similar to solid wood, with better results than particle board which is less dense and tends to chip. This feature allows MDF to be formed with a smooth finish to resemble raised-panel doors. The only drawback however is that unlike solid wood, MDF can't be stained (it has no grain) so it has to be painted or covered in thermofoil.

- Construction

There are two basic types of cabinet door construction - framed and slab. Framed doors are made up of an outer frame that is built around a panel in the center of the door. The edges of the panel fit into slots milled into the inside edges of the frame and are allowed to "float" within the frame to allow for normal expansion and contraction of the wood. Raised panel doors are a common variety of the frame door style.Slab doors don't have the separate parts like a framed door and are usually one-piece construction or the combination of several solid pieces of wood glued and joined together to form a solid slab. Slab doors made from plywood or MDF are covered in a veneer, laminate or thermofoil covering.

Shelves

- Materials

Cabinet shelves are made from one of the engineered wood products - either plywood, MDF or particle board. Regardless of which material is used they're normally covered with another material such as a wood veneer or laminate ply. - Construction

There really isn't much to a cabinet shelf's construction except for the mention of thickness and whether it's built with a reinforcing rail. Beyond that we're just talking about straight boards made out of one of the materials mentioned above.Shelf thickness varies based on cabinet manufacturer and the particular product line (often equating to the level of quality) within a certain brand. Shelf thickness ranges from 1/2" to 5/8" to 3/4" thick. Obviously thicker is better when it comes to longer shelves on wide cabinets in order to avoid sag.

The reinforcing rail is an additional strip of wood that's attached to the front edge of a shelf. It provides added rigidity which is especially helpful in avoiding sag, particularly on long shelves. It's a worthwhile feature if you can find it but it's not a prevalent feature on many manufactured cabinets.

Publisher's Comments

I personally like the reinforcing strip feature for a couple of reasons. A) the engineer in me can relate because there's physical reasons why it makes the shelf more ridid...and B) I have them on my own kitchen cabinet shelves and they work well.

They work because (if they're made correctly) they're wider in one direction than the other. The widest surface is attached to the front of the shelf, giving it more stiffness. It's the same principle as trying to bend a ruler; it can easily be flexed in the 'flat' direction but very difficult if not impossible to bend in the same direction when the wide side is facing you.

The only problem I've found is that this feature is hard to find on mass-manufactured cabinets. You might be able to get a custom cabinet shop to do this for you however.

One variation of this stiffening feature is where the rail is attached to the underside of the shelf at about 1/2 depth.

One additional aspect about cabinet shelf construction lies not so much with the shelf itself but how it's held in the cabinet box and whether or not it's adjustable. Shelves are held in place with a variety of hardware that come in different sizes and materials (metal or plastic).

Cabinet Finish

On wood cabinets the finish is just as important as how well the cabinets are constructed. The finish not only provides aesthetic appeal but is a key component in the protection of the underlying wood surface. It needs that protection from the moisture and chemicals that are typical in a kitchen.

(Keep in mind we're talking about wood cabinets here. Cabinets covered in laminate or melamine aren't coated with these types of finishes and surface treatments.)

The amount of material to explain the science behind the varnishes, lacquers and other cabinet surface treatments could fill a book but it's not necessary for a basic understanding of how a cabinet is put together. What we'll focus on here are some of the common finishes that you're apt to encounter in your cabinet research and their important features.

Materials

These are the most common finish treatments that you'll find on kitchen cabinets:- Paint - The benefit of paint is that you have a limitless color pallet available to you. You're not limited to a range of browns and other earth tones like you are with wood stains. "Milk Paint" is an alternative choice to the standard enamels that are used on cabinetry. It's an organic-based paint made from milk protein, lime and natural pigments. The basic 'recipe' has actually been around for hundreds of years. Milk paint's benefits include it's good durability and strong resistance to water. It also adheres well to wood. It has it's own unique decorative appeal and is reminiscent of the texture of paints used on antique and period furniture.

- Stain - Wood stain is a topical color treatment that alters the natural color of the underlying wood while allowing the grain pattern to show through. Wood stain requires a sealer on top of it for protection.

- Varnish - Varnish is a combination of oil and resin that's used to provide a protective layer over the wood and any other surface treatment like stain. One of the finishing terms you'll probably encounter more often than not is "catalyzed varnish". It sounds high tech and in some respects it is. In more simple terms it defines a type of finish that uses a "catalyst" to cause or speed up a particular reaction between the chemicals in the finish, usually to achieve some specific result. Catalyzed varnish incorporates compounds that make it harder and more durable than it would be without them.

- Lacquer - Lacquer is another top-coat protective sealer used on cabinets and furniture. It's made by dissolving a resin in a solvent. It too can be "catalyzed" and you'll see references to "catalyzed lacquer" in various cabinet.

- Glaze - Glaze is a pigmented but transparent or semi-transparent coating that's applied over a base coating such as paint or stain. Glaze is used to enhance the look of cabinets by highlighting the underlying base color and bringing out surface detail. When glaze is applied and then hand wiped some of the glaze remains in the corners and recesses of doors, providing additional visual highlights.

The Finishing Process

The cabinet finishing process is dependent on the type of finishes used and the individual cabinet maker's capabilities and formula. Large cabinet manufacturers may have sophisticated facilities and processes to apply the finish whereas smaller cabinet makers may take a simpler approach or even farm out the finishing process to a local firm that specializes in that type of work.Wood cabinet finishing involves a number of steps that involve preparing the wood, applying the surface treatments and baking the finish. For an example of one large cabinet manufacturer's method, check out the KraftMaid DuraKraft finishing process. It's an example of the multiple steps that are taken in the cabinet finishing process.

Larger cabinet makers may have the resources and advanced production capabilities to produce consistent quality finishes. Smaller shops may not have the same capabilities. One of the things on your checklist when researching smaller cabinet shops should be their finishing process. Achieving a quality finish requires controlled conditions free from airborne dirt and dust. Some finishes require baking to cure. That's not to say that high-tech production facilities are the only way to achieve a quality finish. Just be sure you understand your cabinet maker's finishing capabilities and whether they'll produce a product that will hold up to the rigors of the kitchen environment.

One final point to remember is that the finish options you choose have a bearing on the final cost of your cabinets. Finishes that include hand-rubbed treatments or multi-step coating applications take time and ultimately raise the cost of the cabinets. Glazing can produce some nice effects but it's an additional step in the process. Ask yourself whether it's absolutely essential in your kitchen style. Otherwise you may be able to save some money on simpler finish treatments.

To learn more about choosing kitchen cabinets check out our Kitchen Cabinets page.

Sources For Getting New Cabinets Installed

When you're ready to get new cabinets you have a couple of choices for getting them installed. You can do it yourself or have it done by a contractor or company that specializes in the installation of cabinetry.

Doing it yourself is certainly an option and you can find plenty of how-to books and guides on how to do it. Just keep in mind that you'll probably encounter walls that aren't square and you'll need to adjust for that as well as other issues that might come up during the installation process.

Publisher's Comments

I got a renewed appreciation for some of the complexities of cabinet installation when we remodeled our kitchen. The installers were in our home for a couple of days. It was rather fascinating to watch them use laser levels and other tools to ensure the cabinets were installed properly and square. It was also clear to me that it's a two-person or more job, particularly when hanging wall cabinets. After that comes the task of installing the doors and drawers and making sure they're straight with consistent gaps.

My advice is this: if you're going to get new cabinets, leave the installation to the pros. They know what they're doing and they've done it many times. They'll be able to do a better job and do it faster than you probably can.

If you need to find a local cabinet professional there's an easy way to find sources in your area using the form below. It'll help you locate one or several potential candidates in your local area.

Here's More Related Info That Might Be Helpful...

Bamboo CabinetsKitchen Cabinet Organizers

Choosing Outdoor Kitchen Cabinets

Buying Kitchen Cabinets Online

Choosing Kitchen Cabinet Hinges

Choosing Kitchen Cabinet Knobs and Pulls

Laundry Cabinets

Garage Cabinets

Publisher's Comments

You'll typically see plywood as an upgrade (and corresponding up-charge) from particle board or MDF from many cabinet makers. Or sometimes the plywood cabinet boxes are only in the manufacturer's higher-end product lines.

Also, be watchful for the terms "solid wood" or "all wood" in a manufacturer's description or literature. "Solid wood" should represent whole, uniform lumber, not a fabrication or wood composite, like particle board, MDF or even plywood.

"All wood" is slightly different in that it usually means all-plywood construction or a combination of plywood and solid wood.

The point is, just be sure when you encounter these terms that you're clear on whether it's truly "solid wood" or plywood so you don't run into any surprises.